May 3, 2018 — In its 60 year history, NASA has launched more than 50 spacecraft to study the solar system beyond Earth and its moon. Despite the long record, the agency's next mission will do something no other U.S. interplanetary probe has done before.

Go west.

Assuming all goes as planned, NASA's InSight lander will be the first mission to study the deep interior of Mars. But eight months before it touches down and begins probing the Red Planet, it will make history becoming NASA's first interplanetary mission to launch from the west coast of the United States.

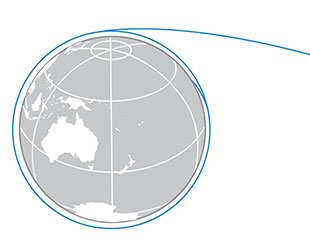

InSight (Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) is scheduled to lift off from Space Launch Complex-3 at Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB) in southern California on Saturday (May 5) at 4:05 a.m. PDT (7:05 a.m. EDT; 1105 GMT). Riding on a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket, InSight will begin its journey toward a November 26 landing on Mars by initially entering a polar orbit around Earth.

East v. West

Since its first attempt in 1962, NASA has launched all of its missions bound for the planets, asteroids and comets from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

At Space Launch Complex 3 (SLC-3) at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, a crane hoists NASA's InSight lander inside its fairing for mating atop a ULA Atlas V rocket. (USAF 30th Space Wing) |

The use of the east coast launch site was a necessity (at least in most cases) to take advantage of the direction that Earth rotates. By heading eastward, especially from a site near the planet's equator, the spacecraft gain velocity from Earth's gravity — enough of an "free" extra boost to make it possible for their rockets and propulsion systems to push them out into the solar system.

In that sense, InSight is no different.

"Earth is going 30 km/s [19 mps]. An Atlas can add a few km/s to that, in a direction we choose. We have to choose carefully or we won't get to Mars," wrote Mark Wallace on Twitter. Wallace designed InSight's trajectory as a mission analyst at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

InSight will launch south-southeast from Vandenberg. That trajectory can lead to Mars as a result of two factors: mass and orbital mechanics.

As interplanetary probes go, InSight is both small and light. The current mission uses the same spacecraft and lander design as the 2008 Phoenix Mars mission, which launched on the less powerful Delta II rocket.

United Launch Alliance graphic showing the trajectory that InSight will follow from launch through departure to Mars. (ULA) |

ULA is in the process of retiring the Delta II, so it put forth and NASA selected the next best option, the Atlas V (401) — which for InSight meant power to spare.

"Launching the InSight mass to the ... Mars targets for its landing site had enough excess performance margin on the Atlas V that both coasts could be utilized," wrote Caley Burke, a trajectory analyst with NASA's Launch Services Program, on Twitter.

The more than capable Atlas rocket will launch InSight into a polar orbit, such that when its Centaur upper stage fires its engine to send InSight toward Mars, the spacecraft will be aimed in the right direction.

Westward Ho!

NASA could have chosen to launch InSight from the Cape, but went with Vandenberg because it had more availability during the mission's launch period.

"InSight is a light vehicle and the Atlas has performance to spare, so the decision was made to go out of [Vandenberg] to relieve congestion [in Florida]," explained Wallace.

30th Space Wing (Vandenberg Air Force Base) embroidered patch identifying InSight as the "1st West Coast Interplanetary Mission." |

Though this is the first time that NASA has proceeded with an interplanetary launch from California, the space agency has considered the option before.

NASA originally intended to launch its 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter from Vandenberg, but ultimately moved it to Cape Canaveral because of the loss of two other missions to the Red Planet, Mars Climate Orbiter and Mars Polar Lander, in 1999. The agency said that the move came as part of an effort to reduce risks to the Odyssey mission.

Specifically, NASA cited schedule flexibility and spacecraft battery margins as the reasons for the switch.

And while every U.S. interplanetary probe up until InSight has left Earth from the east coast, one west coast launch did send a NASA mission out beyond low Earth orbit.

Clementine, a joint mission between the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization and NASA, lifted off for the moon on a Titan IIG rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base on Jan. 25, 1994.