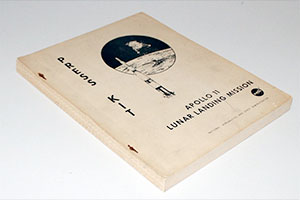

July 31, 2014 — At an upcoming space artifact auction, among the selection of astronauts' autographs, spacecraft parts and mission patches, is a 45-year-old press kit from the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing. Its 250 pages browned with age, it isn't the auction's star lot, but it still could bring in hundreds of dollars.

As memorabilia of the lunar landings, the documents and other materials originally created to sell the public on the idea of sending astronauts to the moon are now on sale as prized collectibles.

But as valuable as the press kits, pamphlets, posters and other ephemera might be on the collector's market today, their significance as a shining example of effective brand marketing may be their true worth.

That's the case laid out — both figuratively and literally — by David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek in "Marketing the Moon " (MIT Press, 2014), a richly-illustrated, engaging coffee-table-style book covering why the secret to NASA's Apollo success was not just its astronauts, engineers and scientists, but also the public relations officers who helped to make "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth" more than just a political tagline. " (MIT Press, 2014), a richly-illustrated, engaging coffee-table-style book covering why the secret to NASA's Apollo success was not just its astronauts, engineers and scientists, but also the public relations officers who helped to make "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth" more than just a political tagline.

"Marketing the moon was a huge success," says Scott, a marketing strategist and bestselling author who notes he's not related to the Apollo astronaut of the similar name. "To deliver 24 men to the moon – 12 of whom ventured to its surface – with 1960s technology, is even more remarkable from our vantage point four decades later. It was a huge project."

"That America spent an average of 3.3 percent of the federal budget on NASA during the peak years from 1963 to 1969, a period when the Vietnam War was in full swing, made the Apollo program not only a remarkable political and technological accomplishment, but also an amazing global marketing and public relations achievement," Scott says.

The story of Apollo has been told many times over, but the angle that Scott and Jurek embraced to their retelling is unique. The two combined their professional experience with their personal passion, collecting space memorabilia — and in particular examples of Apollo-era marketing — to deliver a fresh take on the four decade old quest.

"After years of collecting this material, and lamenting that no book had been written about the subject, we decided to do it ourselves," Jurek, a marketing executive, explains. "We had a literal blast researching and writing the book, and spending hours and hours talking to former NASA public affairs office legends, as well as former contractor marketers and the astronauts themselves — talking about and listening to stories we'd never heard before, because no one had ever asked about them."

"And that was our goal for the book, not to rehash material that had been discussed before, but to truly uncover those unique and wonderful stories that could bring to life this overlooked aspect of Apollo," Jurek says.

Even if you're not a marketing professional, "Marketing the Moon" is a visual treat. The authors included almost 300 illustrations, curated down from an initial collection of over 3,000.

"Many have never been published before," Jurek says of the book's images. "And the effect, with the narrative, the illustrations, and the sidebars, is that of having a museum exhibit in one's hand. That was [also] one of our goals and I think we achieved that."

Scott and Jurek spoke with collectSPACE during a recent interview about collecting and marketing the moon.

collectSPACE (cS): "Marketing the Moon" is as much a case study in marketing as it is a guide to what has become prized memorabilia of the moon landing. Why do you think Apollo marketing materials resonate with collectors today?

David Meerman Scott (DMS): Unlike spacecraft artifacts, collectables and signed photos, marketing materials show the design of the times. With brochures, advertisements, product packaging and TV commercials, we are instantly brought back to the Apollo era of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

cS: What is your favorite marketing memorabilia from the book?

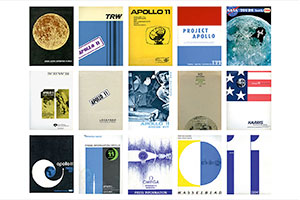

DMS: I absolutely love my collection of contractor press kits from Apollo 11. These press kits provided valuable additional information not found in NASA-issued releases. Reporters and editors working on stories about the lunar landings had access to such documents from more than one hundred manufacturers. I love the artwork and design of the kits.

Guaranteeing that a kit of materials would stand out from the crowd was no easy task. A mere release together with press-ready photos tucked inside a pre-printed folder was not enough when hundreds of other public relations people were also courting the media and handing out documents. But a creatively produced press kit with well-presented, clear, informative materials often captured attention and led directly to mentions in the media.

As an Apollo collector, as well as a marketing and PR strategist, these things resonate with me personally as an intersection of two interests. I have more than 50 of them from companies that built Apollo spacecraft parts, such as Boeing, McDonnell Douglas and Grumman, and from the manufacturers like GE, Avco, and Bendix, and consumer product companies who developed items for astronaut use such as Omega (watches) and Stouffer's (food served in the mobile quarantine facility). These lavishly illustrated press kits tell a fantastic story. While I cannot be certain, I believe I have the most complete collection of Apollo 11 press kits.

Richard Jurek (RJ): I love the vintage documentation we used inside the book, from the flown "Are You A Turtle?" cue card from Apollo 7 to the original public affairs plan for Apollo 11. They are time-capsules of the period and speak volumes about the approaches and attitudes of the time.

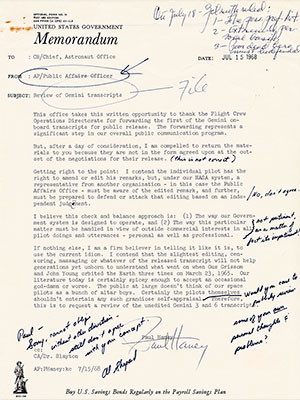

I am particularly fond of a specific letter between public affairs officer Paul Haney [the voice of Gemini and Apollo mission control] and astronaut Alan Shepard, and what it represents in the battle between the astronaut office and public affairs for real-time access to the missions, and the desire of public affairs to fulfill the NASA communications mandate with unedited transcripts.

This "open program" struggle and tension illustrates the hard work that was necessary by the public affairs office and those folks behind the scenes as they coped with this massive, sustained real-time event. I view that letter as a seminal document in American press freedom.

cS: Were there any marketing materials that you knew existed but had no luck in finding for use in the book?

RJ: It's impossible to research all of the internal memos, documents and letters as were issued by the public affairs office and staff, just because of the very ephemeral nature of this material, and the difficulty tracking it all down from various archives, private collections, and the like.

As a NASA and PR and marketing junkie, I could spend a lifetime reading through that material. But you have to pick and choose your battles, and given the massive amounts of research we did for the book, and the original source material we explored – from primary interviews with NASA PAO staffers, the contractor marketers, and the reporters themselves, in addition to countless memos, reports, and documents – we endeavored to highlight key, instructional moments, like with the Haney/Shepard letter.

cS: What is the 'holy grail' for a collector interested in the marketing of Apollo?

DMS: Rich has been fortunate to acquire two things that appear in the book that are particularly fantastic — the cue card used on Apollo 7 and the letter from Paul Haney with Alan Shepard annotations.

From my collection, I think the most historically important piece is my Apollo 8 RCA slow scan TV camera training unit. It was used in training for Apollo 8 and is signed by that mission's crew.

Ask anybody over the age of around 50 about the moon, and, like me, they'll talk about the amazing live television broadcasts from the lunar surface. I was eight years old when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed their lunar module Eagle on the moon on July 20, 1969. I remember when subsequent missions occurred during school days, televisions were wheeled into my classroom so we could watch liftoffs, lunar EVAs and splashdowns.

Live television from the moon, conceived and developed by NASA in partnership with many contractors such as Westinghouse and RCA, was the ultimate in marketing of the Apollo program.

There's no doubt that live television from the moon is one of the most memorable human legacies of the twentieth century. It is an epic story of visionaries struggling against entrenched notions of access and information distribution. That this content, which was conceived and paid for by NASA in order to educate and inform both the American public who was paying for the program and the rest of the world's population that was in awe of America's technical prowess, presents a fascinating business case study that teaches modern marketers a great deal.

RJ: It also depends on your interest — and there are so many nuances.

If you are more interested in the commercial aspects of Apollo, a flown item with a strong commercial brand, like one of the Sony cassette tapes or a Garland mechanical pencil might fit the bill, as those items can be displayed along with period advertisements, press kits, and vintage marketing material to complete the suite.

For others, and myself in particular, the "holy grail" of material happens to be the original manuscript material of key moments, such as the original Paul Haney reporter's notebook in my collection from the Apollo 10 crew press conference, where Haney writes down quotes from Gene Cernan apologizing for swearing on the open mic, or one of the original private services contract with Harry Batten signed by all of NASA's Group 3 astronauts, that spell out the commercial representation of the private interests of the astronauts.

These original documents make real the historic moments and provide access into the nuances and subtleties that are often left on the cutting room floor by the sound-byte nature of our world today — and present a fuller, more complete picture of the times.

cS: With the benefit of four decades of hindsight, was the effort to market the moon ultimately a success? Man walked on the moon of course, but contemporary polls found that the public was never wholly in favor of any of the moon landings, and the program could not be sustained after only a relatively few flights.

Was this a failure of selling the program or a flaw in the way Apollo was structured?

DMS: During the Apollo years, NASA was a government agency that got it right.

Arguably more than anyone else, it was President Dwight D. Eisenhower who got the story right and President John F. Kennedy, who put the big wheels into motion, but who saw it all mostly in Cold War terms, sided with the angels when it came to selling the big idea.

"I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish."

Kennedy led the nation on a classic quest. He defined an adventure and his powerful story was a motivation to act. The three elements of a quest are part of his challenge: the hero (this nation); the goal (the moon and back safely); and the hardships along the way ("none will be so difficult or expensive").

By invoking a quest, President Kennedy motivated us to be interested and that the goal would be worth achieving. And most of America was behind it.

Eight years later, we achieved Kennedy's goal and people celebrated widely. Some 400,000 people and many billions of dollars were involved in getting the astronauts there.

But then we were done. The goal was achieved. The other Apollo missions did not matter to the goal. Apollo 13 was another great story but for the potential failure averted.

The story that was told to get us to the moon succeeded, but there was no compelling story for additional missions or for going anywhere beyond the moon. That's why we've been stuck in low Earth orbit since Apollo.

If we are ever going to conquer space again, we need a powerful story to get us there.

RJ: NASA's pioneering brand journalism and embracing of the open program, and hiring of ex-journalists to conduct their public affairs efforts was a brilliant move, and allowed for a hugely successful public affairs effort.

To facilitate open and complete communication with the public is a responsibility embedded in NASA's charter as a civilian government organization, and [the space agency] performed brilliantly in this role, even up to today. NASA is brilliant at PR and communications, and they are often at the vanguard of modern techniques, as evidenced by their recent Webby Awards.

The agency's failures though, are ones of structure, as the traditional functions of marketing are not within NASA's purview. In fact, NASA gets slapped on the wrist when it attempts to market, versus communicate. The traditional modes of marketing during Apollo were conducted by the program's contractors — Boeing, Raytheon, Grumman and the like.

The bumpy nature of public support and interest in the myriad of follow-on and post Apollo programs underscore this fact, and I often talk about the failure of managing the product life cycles for NASA programs — a responsibility that does not rest with NASA, but with the President and Congress, which exposes NASA to the fickle nature of term politics and ever-changing priorities.

cS: Apollo 10 commander Tom Stafford once opined that if the internet existed during the days of Apollo, we'd never have reached the moon. He was referring to "armchair engineers" who reach out to politicians and the press when things go wrong and when they disagree with the approach that NASA is taking. Do you agree with Stafford's conclusion?

If it existed in its current form in the 1960s, would the internet have been a help or hinderance to the efforts to market the moon?

RJ: I tend to agree with him, in the sense that the internet and its countless alternative sources for news, information and opinion are analogous with the challenges faced by media companies trying to gain an audience and market share in a world of thousands of channels and streaming options.

It is so hard to generate a base of support large enough to sustain a major effort over any significant length of time. Our attentions are so fractured, and it is easy to confuse initial enthusiasm with dollars-through-the-door support.

DMS: Marketing, and getting a lot of people behind an idea, was much easier in the days of three TV networks, daily city newspapers and general interest magazines like LIFE.

cS: Today, NASA's ultimate goal is sending astronauts to Mars. What lessons from marketing Apollo can be directly applied to NASA's current efforts to sell the nation on Mars?

RJ: This is a complex issue with a lot of different opinions and approaches. Strictly from a marketing standpoint, the challenges NASA has is one of resource allocation and scope creep. The space agency has so many wonderful and competing programs, that it is hard to fund them all, and at the same time, embark on an audacious and bold mission like going to Mars.

In its never ending pursuit of political support and funding, NASA has grown into an agency that is attempting to be all things to all people – and it just isn't possible to fund all of the fantastic and important research and programs that currently fall under its budget. So, from my perspective, NASA needs a global imperative, and a unifying mission, around which it can focus all its efforts. Those that don't fit, perhaps need to be spun off to other agencies, or into the private sector.

But NASA should be in the business of driving the bold initiatives and goals, and letting the private sector — like it did in the days of Apollo when 90% of all people working on the effort were employed by the private contractors to the program — do the rest.

I think it is important to look to the past to inform how we approach the future. As the goals of the nation solidified around space exploration in the late 1950s, NASA was formed out of NACA (the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics) and existing military missile programs into a new civilian agency. Perhaps the new bold audacious goal of going to Mars needs that same sort of bottom up re-engineering and thinking.

Marketing the Moon by David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek was published by MIT Press in Feb. 2014. |

|

In "Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Apollo Lunar Program" co-authors David Meerman Scott and Richard Jurek reveal how NASA built its case to send astronauts to the moon. (WebInkNow)

A 45-year-old Apollo 11 press kit for the first lunar landing in July 1969 today could sell from hundreds of dollars. (Lunar Legacies)

Cover art for "Marketing the Moon" by Scott and Jurek. (MIT Press)

A colorful collection of original Apollo 11 press kits. (MIT Press)

Memorandum from Paul Haney, NASA's Apollo-era chief of public affairs at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, annotated by Alan B. Shepard, Jr., chief of the Astronaut Office. (MIT Press)

NASA public affairs staff shown working in the Mission Control Center in Houston in June 1965. From left to right: Bob Hart, Paul Haney, Al Alibrando and Terry White. (MIT Press/NASA) |