December 5, 2002 — I am inside the International Space Station.

To my left, I catch a glimpse of Earth's limb, breathtaking against the blackness of space.

In front of me, Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev float in my direction.

Turning my head to the right, the commander of the first crew to inhabit the station, Bill Shepherd, is watching his crewmates with a smile.

The appearance of being aboard the station is, sadly, an illusion — a remarkable giant-screen movie by IMAX, filmed in space. Bill Shepherd, however, is real, and sitting right next to me. I am seeing footage he shot as vividly as if I had flown to the station with him, while he is enjoying reliving moments from his remarkable flight.

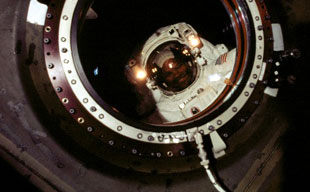

Space Station, the latest in a magnificent series of space films from IMAX that began with the first shuttle flight, chronicles the on-orbit construction of this new outpost and allows us to observe everyday life on-board the ISS with the first crews. At a time when many are questioning the purpose of space station, it is a stirring reminder of why mankind should be in space. Bill and Beth Shepherd were the special guests for the San Diego premiere of the movie at the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center, where they discussed the background to the events portrayed in the movie.

Bill Shepherd believes that the film, which is being shown all around the world, will help to reawaken enthusiasm in the space program.

"We have a space program that is really fueled by the interest and support of people across the country, so it is important that we have kids and adults who are educated about why we do these things. I think the interest kids have today is high, but not as high as I remember it during the 'heroic' period of the early days of space. The IMAX movie is a forty-minute movie that was shot by twenty-five specially trained astronauts and cosmonauts on orbit. We flew nine missions to make it, and filmed about thirteen miles of film. It's a very special film, in a unique format. It shows the construction of the space station and the first couple of crews who were onboard. The film puts me right there, right back in that environment, and reminds me of my flight; it gives you a chance to join us and see what it is like to live and work as a member of the crew. We tried to give you that sense as a viewer. In addition, you'll see some exterior shots from the space shuttles that came to visit us, that are just spectacular stuff!"

Shepherd's command of the first space station crew was the culmination of a long career as an astronaut and a naval officer. His father was a World War II Navy veteran and aerospace engineer, and Shepherd enjoyed growing up around boats and water. Towards the end of his high school education he had already decided upon a career in the Navy. He planned on becoming a naval aviator like his father, but did not pass the eye exam, so he became a diver instead. With degrees in aerospace, ocean and mechanical engineering, he served as a Navy SEAL, with the Navy's Underwater Demolition Teams and the Special Boat Unit.

Shepherd's command of the first space station crew was the culmination of a long career as an astronaut and a naval officer. His father was a World War II Navy veteran and aerospace engineer, and Shepherd enjoyed growing up around boats and water. Towards the end of his high school education he had already decided upon a career in the Navy. He planned on becoming a naval aviator like his father, but did not pass the eye exam, so he became a diver instead. With degrees in aerospace, ocean and mechanical engineering, he served as a Navy SEAL, with the Navy's Underwater Demolition Teams and the Special Boat Unit.

"I have just retired from the Navy — I was a Navy SEAL for thirty years and five months. I wanted to fly in the Navy, but didn't really get the chance. I worked as a SEAL for thirteen years before going to NASA for seventeen years as an astronaut. When NASA started making the shuttle program happen, it was clear that astronauts would do more than just flying. I applied to NASA, and it took me two go-arounds to get there, but finally in 1984 I was selected as one of the seventeen people in the tenth group of astronauts. I don't really know why NASA picked me. I went to MIT for three years for the graduate program; it included ship design, and that really turned out to be propitious. I do think that NASA is particularly good about not picking everybody from exactly the same mold, and that is one of its strengths."

Commanders of shuttle flights need to be pilots — however, for the space station, Shepherd's skills would prove to be more useful for the tasks and trials that lay ahead. For example, he found his experience as a diver of considerable help when working with spacesuits.

"The background of astronauts and cosmonauts runs the gamut. It's hard to get to be an astronaut — you have got to go through a lot of school — probably fifteen years of school. I did nineteen years, and wish I had done a little more. We have two categories of American astronauts. One is professional pilots with extensive experience in high-performance airplanes and testing; these folks mostly come out of the military, because that is usually where you get that kind of experience. They make up about thirty-five to forty percent of the astronauts in Houston. The other folks are Mission Specialists; they deal with the systems on the shuttle, act as flight engineers, operate the robotic arm and do the space walks. These folks are all engineers, scientists, doctors, and we have some veterinarians. No lawyers yet, but maybe that's coming! Mission Specialists are heavily involved in putting together and running the space station. The piloting tasks for the station are pretty limited, except for the Soyuz driver — it is more of a leading and managing task, so we don't have to have career pilots doing it."

Shepherd's astronaut career began the same year that President Reagan gave NASA the task of creating the space station, initially called "Freedom." It is a sad reflection on the lumbering pace of that program that Shepherd had made three space flights, over two decades, before he became its first commander. Originally slated to begin operations in 1994, political and management problems saw the station scaled down, costs escalate alarmingly and launch dates slip repeatedly.

Shepherd's first flight was shuttle mission STS-27. In common with the classified nature of Shepherd's Navy SEAL activities, this was a top secret mission for the Department of Defense. It was later reported that a satellite was placed into low Earth orbit to carry out military radar reconnaissance. Despite the hurried pace of the mission Shepherd still had time to enjoy his first experience of seeing the Earth from space — views that sometimes reminded him more of Jupiter's Europa than a familiar home planet.

"I flew my first shuttle flight in 1988 with a crew of five guys. We had a four and a half day mission — boom, boom, up and down. The first day was very busy. On the morning of the second day I got up early, and had a chance to drink a cup of coffee and look out of the window before they got set up. The shuttle flies upside down, so you look out of the overhead window and see the Earth below you. It was winter, and this particular moment was over Siberia. I could see snow everywhere, as far as I could see. There was not any feature I could see that was recognizable — no contrails, no railroad tracks, dams, roads — nothing. I looked out and thought there was no reason why this could not be the surface of some other planet."

Shepherd also flew STS-41 in 1990, helping to deploy the Ulysses spacecraft to study the Sun, and 1992's STS-52, mapping the Earth using lasers. Following his third flight, Shepherd was assigned in 1993 to a management position within the space station program. Shortly afterwards, the Clinton administration demanded a total overhaul of the program — one that would include the Russians as partners. By combining Russia's plans for a Mir space station successor with the American efforts, it was hoped that the pooling of resources, talent and political will would revive a project in dire financial straits. The reality proved to be quite different. Delays on both sides, broken promises and even disputes on what to call the station hit the program with dispiriting regularity.

Shepherd tried to concentrate on the positives — always keeping in mind what the station could achieve in the long term. Looking into the history of space planning, he believed that the primary purpose of a space station was to allow humankind to live off-planet on an almost permanent basis. As well as being a place for research possible only in space, Shepherd thought that the future station would allow opportunities for humans to travel to other places, far from Earth. He believed that it would be a long time, if ever, before a space station would be able to pay its way by manufacturing items on orbit. Instead, solving the engineering difficulties of creating a station was enough justification for its existence. Learning assembly techniques in Earth orbit, as well as designing modules with long-term electrical and environmental needs would be a large step in designing spacecraft that could voyage to Mars, he hoped.

"Everybody is hoping that the space station will produce a lot of Nobel Prize winners — and that may come. We may invent new drugs or electronic components that cannot be made on Earth. That's why we really built it, but whether that comes to pass or not is not the essence of it. The issue is that we have humans in orbit who are off the planet — they do not live on Earth anymore. They are not going to be there forever, granted; they are going to have mission durations from months to maybe a year. But we are taking the first steps in trying to define the place and role that humans have in this universe. The question is, are humans going to inhabit the Earth, this magnificent azure-blue globe that we live on, and that is it? Or are we destined to travel, live and work elsewhere? I don't know if the space station is going to answer these questions — but we are on the trail of those answers."

In the meantime, there were more down-to-Earth problems to overcome. With seventeen different countries building and supporting the project, Shepherd found that each had a different style of operation — particularly when it came to the differences between American and Russian technology. He considered merging those methods into a harmonious whole the biggest challenge of all. Shepherd discovered that other nations might approach a problem in an entirely different way to NASA, and understanding these "technical cultures," as he puts it, was just as crucial as understanding the actual hardware. Old habits and methods had to be reassessed, as well as an open, candid evaluation of sometimes differing practices routine to other agencies.

"I was absorbed into a very contentious program. President Reagan had said we should build a station in space, and in 1993 I was assigned to a management team that restructured and tried to bring order to what had been eight years of chaos. Tying the pieces together and making them work was one of the success stories of what we are doing, and we paid a lot of attention to that. The cosmonauts and the astronauts got on well, as did the engineers and managers. At the worker level, that work all went very well. When you got to the higher echelon of management, the politics and the diplomats, that is where it all broke down."

At the very end of 1995, Shepherd left his management position, but stayed within the program — he was named to command the first resident crew. At the time, the launch was only supposed to be a year away. However, further delays with launching station hardware brought this date closer and closer to the turn of the century. Meanwhile Shepherd and his cosmonaut crewmembers, Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko, patiently continued their training.

"I lived and trained in Russia for about five years. Five years, just for this one flight. That was longer than all of the time I spent in college! We did survival training in the Black Sea. If we'd had problems on the space station we had a little capsule we could get in, like a lifeboat. We might come down in the ocean somewhere, or end up in the woods in winter — so we practiced that in our training. We would build a little shelter, light a fire and wait for people to find us and pick us up. We practiced being weightless underwater in the training tank in Houston — the largest swimming pool in the United States. My wife Beth was part of the team who trained us to get ready to fly, both in Houston and in Russia."

Bill Shepherd married around the time he was named to the ISS crew. As his wife Beth was also working on the mission — as NASA's physical therapist assigned to the crew — she consequently saw far more of her husband than most other wives of astronauts training in Russia. However, despite her involvement, there were still long and difficult months of separation, as she recalls:

"Initially, with the training, he was gone six months at a time, and luckily I did go to Russia and see him, because of my job. I probably got to see him more than other families, but it might have only been once or twice a year that we actually got to spend time together. So that was hard — but you get used to it. The training was supposed to only be two years; they were going to launch in 1998. It kept getting pushed back, and that is when it started getting frustrating — could we just get this over with? Please?"

The years of training, and Bill Shepherd's prior experiences as a program manager, allowed the ISS crew to bond and solve problems as a team. Being the first crew, Shepherd realized they would be the ones to iron out many of the problems and set the tone for the future. All too often the crew found themselves in the position of being the middlemen for disputes between the US, Russia and Europe, devising their own solutions and persuading the various sides to accept them. Many of the issues were cultural — for example, some countries commonly used switches that twisted to turn equipment on or off, and were not used to those where up meant on and down meant off. It was similar to creating a whole new language from scratch. Shepherd, mindful of the future, imagines that many of the compromises and solutions reached will prove to be cornerstones of international space efforts for centuries.

To Shepherd's delight things finally began to progress in 1998, as modules of the station began arriving on orbit.

"The first piece of the space station was launched on a big booster from Kazakhstan. A month later, a shuttle went up with the first US piece. The shuttle docked to it and joined the two modules, Russian and American, together. The shuttle crew went inside, including Sergei on that flight."

It would be another two years, however, before the crew quarters were finally ready to be launched from Russia, clearing the way at last for Shepherd's crew to begin their mission.

"In the summer of 2000, we were back in Moscow, looking at the inside of the module we would live in being finished in a factory. That went up late in the summer, from the same launch pad in Kazakhstan. We finished our training in Moscow, and went down to Kazakhstan to get ready to launch. They have a very extensive museum of space flight history, kind of like the Air and Space Museum in the USA. Right next door is the cottage where Yuri Gagarin lived in 1961. Three days before our launch, the rocket we were to fly on goes out from the assembly building to the launch pad on a railroad track. The pad is about three miles away, and when they get the railroad car to the right spot they push the rocket up, until it is sitting on its pad, ready to fly."

Shepherd was more than ready to go. In the years of waiting, he had been given plenty of time to ponder what it would mean to be the first commander, and what kind of tone he wanted to set. He had always been fascinated by seafarers' lore, and believed that the space station would benefit greatly from some naval traditions. When he learned that America's first ever space station crew, commanded by Pete Conrad, had been all-Navy and had used naval practices, he planned to emulate their example.

"I really think that the technical thinking, the culture that we need to be involved in now is much more of a ship mentality than an airplane one when it comes to the space station. Let's say that we build vehicles to go to Mars or somewhere else. Right now, we have everything managed fairly intensely from the ground by people who are essentially air traffic controllers. We are not going to have that when we go to Mars — the communication delays are so extensive. We are going to be self-contained, on our own. If something breaks, we are going to have to fix it. This is not airplane thinking, this is shipboard thinking. There are a lot of other angles to it. We are using the skills, talents and insights of astronauts from sixteen countries. Maybe we do not have all the answers here in the United States. We are learning that in fact is the case."

Self-sufficiency was the key to what Shepherd planned in commanding his orbiting vessel — to fix whatever broke down and make do with what was on board, like a ship away from port. He likens the mission to taking a new ship or submarine out on its first sea voyage — a "shake-down cruise." Tellingly, one of the books he planned to read while in space was Richard McKenna's novel, The Sand Pebbles. This story of a US Navy gunboat patrolling the Chinese coast describes how the crew gradually gains a deep appreciation of a country that at first seemed very alien to them. Their former, distrustful feelings change to open-minded humanity. In contrast, the ship's inner workings are unforgiving. Learn their workings, and they will run smoothly; make hasty assumptions and they will fail. The book was the perfect parable for the mission ahead.

On October 31st, 2000, the moment that Shepherd had worked for all these years finally arrived. Waving and smiling, he gave onlookers a cheery thumbs-up sign and called out "Let's do it!" as he made his way to board the Soyuz spacecraft.

On October 31st, 2000, the moment that Shepherd had worked for all these years finally arrived. Waving and smiling, he gave onlookers a cheery thumbs-up sign and called out "Let's do it!" as he made his way to board the Soyuz spacecraft.

"We got up early in the morning, had something to eat, got ready to leave the crew quarters we were staying in and go down to the rocket. We put on white pressure suits — after we got those checked out we came out, Yuri had to salute the general, and then we went out to where the rocket was. We went up in an elevator to the top of the rocket and entered the capsule. Before we did that we got to wave goodbye to everyone. At about ten in the morning, they started the engines."

Beth Shepherd, as an active participant in the mission, had a different perspective on the launch than many would expect of an astronaut's wife. It had been a long and worthwhile wait for her as well.

"There were a lot of anxious moments. A month before launch was one of them, because there was so much to do, and everybody wanted a piece of him. There is always a joke that the husband has a major 'honey-do' list — well, I had a list, which never ended, even when he was flying. Considering I had already been working at NASA for four years, I had already experienced many people I had trained being launched as I watched. The first eight minutes is the critical time, when you particularly don't want anything bad to happen. I had had a lot of time to think about it too, so on launch day we were finally seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. I was excited for him!"

Bill Shepherd considered his mission "the keystone for the future of human space exploration," an opinion echoed by a number of NASA managers. Barring any unforeseen circumstances, they said, it was the very last morning in human history when there would be no humans off-planet. Shepherd, having previously flown into space on the shuttle, would commence this new space flight era on a Russian rocket.

"The shuttle and Soyuz launches are pretty similar. You are essentially on your back, in a couch in the Russian Soyuz capsule, and sitting in a chair that is laid back on the shuttle. The Russian rocket is a lot more crammed, but the sensation is very similar. These are liquid engines, so when you first start you don't want to let the rocket fly until the engines are at full thrust. So there are about five or six seconds when the engines are spooling up, getting to their full power, and you are not going anywhere. On the shuttle, you have the big solid rocket boosters, which develop thrust really quickly. It's kind of like being in a car and getting rear-ended mildly by a car going at ten miles an hour. You feel a whoomp, then pressure on your chest, which builds up. You are really going through three times the force of gravity — it feels like a heavy person standing right in the middle of your chest. That goes on for a little over eight minutes, until you get into orbit. There, everything unloads, starts floating around, and you are weightless."

Despite being the ISS commander, Shepherd's job on the flight to the station was basically to stay out of the way. While Gidzenko flew the spacecraft and Krikalev ran most of the spacecraft systems, Shepherd occupied himself with running the radio and some of the life support equipment.

"We lived in the small module on top of the capsule we flew up in for about two and a half days — we were behind the space station, and had to catch up with it. We were going seventeen thousand miles an hour, chasing that space station. To sleep, we had to tie ourselves to the wall with little straps, so we didn't fly around."

On November 2nd, the Soyuz spacecraft docked with the space station's rear port. Just over an hour later, with pressure checks completed, the hatches were opened. Shepherd was ready to "make the ship come alive," and the crew eagerly began their work onboard.

"We docked right to the back of the station. Going inside, we opened it up and turned the lights on. It was the first time that crews were living aboard, and we spent a couple of months in the winter of 2000 turning all of the systems on. What was really fun about being in space was doing that kind of work. One of the things I most enjoyed about working on the space station was that, once we got into orbit, we ceased being American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts. We thought a lot about this before we flew — when we were in space, we were really emissaries of something different We were an entity that really did not belong to one country, that represented hopefully the ambitions of the species."

A good deal of hard work lay ahead of the crew. With one of the station's modules closed to them, their tasks would involve turning on and testing systems as well as moving bag after bag of supplies that cluttered the noisy working spaces. This was not the gleaming, spacious station of science fiction — not yet.

"The shape of the space station is pretty much done to try and create modules that can be lifted by the rockets we have now. We are limited to schoolbus-sized modules that weigh approximately twenty to twenty-three tons, depending on which boosters are picking it up. The wagon wheel shape of space stations you see in science fiction movies was a concept so they could be spun, to generate artificial gravity. The jury is still out on the amount of gravity that could be generated by centrifugal force in space — it might be a third of a G. We do know that individuals in a rotating room get nauseous if the room is rotating above a couple of degrees a second. Putting those two together, where you have a space station creating a third of a G, with the angular rotation rate to be no more than a couple of degrees per second, you end up with a wagon wheel that is about half a mile across!"

The crew activated the life support system, installed computers and radios — a lot of "bolting things down, wiring things up and punching buttons to make sure that they run right," as Shepherd described it. He compared it to moving into a new house, where all the utilities need to be set up and checked. It was necessary for the crew to put in very long working days if everything was to be made ready for the delivery of the station's first science laboratory module.

"When you are up in space, you have to be part of a crew, which means you have to know how to do everything. If you have an emergency, if something bad happens, you have to know how to deal with that — maybe even get in your capsule and come home. It's not something that anyone could just step into and do — you have to have a lot of training. It takes years. We spoke about half Russian, half English. We went back and forth in a mixture of English and Russian, and sometimes our sentences would contain English and Russian words. We'd call that 'Runglish!' One of the guys, Sergei, had excellent English, so it kind of went back and forth. Both Yuri and Sergei were fluent in English, but Sergei was exceptionally so. He's basically a native speaker. My conversations with the ground for four of the five months were 100 percent Russian, talking almost exclusively to Mission Control in Moscow. Of course, we talked to Houston too, but all of the control was being done in Moscow. There's a whole different alphabet in Russian — it's not enough just to learn the language, you have to learn a whole different alphabet too."

The international nature of the venture was exemplified by Krikalev when he stated that, when fastening bolts inside of the station, he honestly did not care if it was "for Russia or for America."

There were some aspects of naval tradition that Shepherd planned to commence the moment he arrived. Ships of exploration always have a name, and the space station had gone through a large number of possible titles over the decades without any real decision being made. In a Navy tradition built on thousands of years of human seafaring, Shepherd felt the station should be named as early as possible, to bring success to the voyage and good luck to the crew. Having pressed for a decision to be made for years before the flight, he decided to take matters into his own hands once onboard. Krikalev agreed with his choice of "Alpha" — it was neither Russian nor English, instead going back to the common root of both languages. In Greek mythology, it was the high point to which humans could ascend to achieve contact with the heavens. In the first few hours aboard the station, Shepherd put NASA's Administrator, Dan Goldin, on the spot with a request to name the station. Goldin grudgingly agreed that Alpha could be the call sign for the duration of Shepherd's stay.

Another Navy tradition Shepherd took to orbit was to begin a ship's log. His entries in the log give a vivid description of the amount of work the crew had to carry out getting the station shipshape. Equipment and tools had to be located from the bags of gear filling the station. Despite the years of planning, Shepherd knew that this was a test program, and there would be many unexpected challenges with hardware and software. Some systems, such as the thermal control system, could never be fully tested on the ground — they would have their first true trials in space.

NASA was used to scheduling crews for work aboard shuttle missions, where everything is carefully orchestrated to account for every moment. On the space station, Shepherd planned to review the day's tasks with mission control every morning, then get to work independently. It seemed that NASA had not learned those changes fast enough at first, as the crew soon fell behind the timeline that mission control tried to impose on them. Equipment did not work, or took far longer to use than planned. A food warmer designed to be installed in half an hour took one and a half days to get running. Wires, cables and other equipment were not where they were supposed to be, leading to hours of searching through lockers. Inadequately translated instructions to install equipment created problems that a good diagram would have avoided. Shepherd accepted that the crew would push to get thirty hours of work done in each sixteen-hour day, as this would make things a lot easier for subsequent crews. A garage tinkerer by nature, he spent spare moments and time off repairing station elements, and routinely worked into the time he was supposed to be asleep. With an inadequate supply of tools, he would often use his Navy SEAL knife for repairs. There were major frustrations — the short amount of time available to talk to the ground delayed talking through solutions to technical problems, and often mission control did not keep up with the adjustments to the schedule that the crew needed. Shepherd stayed positive on the whole, citing the Civil War adage stating when you have a devil of a day, you plan to "lick 'em tomorrow." Occasionally, however, on a bad day, he'd cite the Navy SEAL saying: "the only easy day was yesterday."

Exercising took up a large amount of time, too. Shepherd knew how important it was to stay healthy in space, and that exercise would help counteract some of the negative effects of zero gravity.

"Exercise was a big part of our day — we did it twice every day. We had a bicycle, a treadmill, and I practiced on a kind of jungle gym that we had, which turned out to be a pretty good thing to do. Early on in the mission we would talk to the doctors every day, just so they could see how we were doing. We had a pretty strict program that would start about two weeks before launch. They isolated the crew from people who have not been screened by the medical people, to see if they are not carrying something that is contagious. They try and keep little kids away, as kids get sick a lot more than adults do. People who had families had to leave them two weeks before flight and go into a special living area. That has been very effective in keeping infectious diseases down on space flights. For more serious things like appendicitis, we would probably not have kept somebody in orbit. We had the capability to get into that little capsule and come home. The three people who came up in that would have to come home in it, so we'd secure the station, all get in that capsule and come home. That whole process could take six to eight hours to get down — not ideal, but it would do."

Beth Shepherd hoped that the physical conditioning she had done with the crew prior to the flight would pay off.

"Astronauts chosen in the early days were military people who were doing P.T. three days a week whether they liked it or not — it became a way of life. That carried over into the astronaut program. It was unknown what the physiological effects were going to be, so there was more intensity on being physically prepared. Once we had a few more answers with Skylab and the shuttle program and realized we could being people home safely without worrying so much about their physical condition, it was not important again until we started doing the space station. We knew that we were going to be keeping people up there for longer than a ten or sixteen day mission. We know that, past ten days of zero gravity, we start seeing cardiovascular and muscular atrophy. It is not until thirty days of space flight that you start seeing any type of bone loss. The big issues that we learned from having our astronauts fly on the Russian space station Mir was that if they lost bone in flight, they did not always recover it when they came back home. We still have several people from the Mir program who are not back to their baseline bone. If we are going to go to Mars, with the rockets we have now it would take us almost a year to get there. They are expected to work once they get there in a gravity environment with a heavy suit on, so we want to make sure that they are in pretty good shape so that they are not prone to injury when they get there and cannot do anything. There has been a huge emphasis on getting people physically prepared and figuring out how can keep them physiologically sound, so that we can go to Mars. The number one way we know to prevent bone loss is weight training. We have a resistive weight training device on board, and we are also looking at supplements and drugs."

Life onboard was not entirely devoted to engineering and exercising. To relax, the crew watched a number of movies. Bill Shepherd enjoyed trying to work out what movie Gidzenko would pick to watch each night, soon realizing that Arnold Schwarzenegger was a favorite. Watching "Carlito's Way" with Russian subtitles, Shepherd soon realized that his Russian language lessons had not taught him the slang of gangsters. He also found himself having to explain the meaning of the term "chick flick" to his Russian crewmembers. Watching military movies such as "Full Metal Jacket" and a history of the SEALs, Shepherd found they were useful ways to demonstrate how he planned to integrate military traditions into station life.

On November 16th, the Progress M1-4 unmanned resupply craft was launched, rendezvousing with the station two days later.

"We had an unmanned cargo ship that came up a few weeks after we got there. It brought food, fresh water, oxygen and spare parts — a lot of things we needed. Every couple of days we would take out the trash. We would load it into the Progress module that we had taken our supplies out of. We would tie everything down in it, then deorbited it and it would burn up in the upper atmosphere."

Docking this cargo ship, however, would not prove to be easy. The automatic docking system did not work, and the Progress began flying erratically, wobbling uncomfortably close to the station. Despite problems with the TV camera image, Gidzenko managed to dock the Progress manually. Once docked, the crew had the challenge of getting all of the supplies, ranging from water to computers, unloaded and stored correctly. Shepherd likened it to having presents tidily wrapped under a Christmas tree, then unwrapping them and finding they now took up the whole room. The tightly packed supplies in Progress took effort to be put away correctly in the already cramped station — then the process of tightly packing the supply craft with trash had to begin. With a space shuttle visiting not long afterwards, there was a great rush to complete these tasks. On December 1st, the Progress was undocked, and as Krikalev tracked it with the laser range finder, Shepherd watched it pulse its thrusters to back away from the station, then fly below and behind the station, into the sunlight.

That same day, space shuttle Endeavour was launched on the STS-97 mission to Alpha. Their main task was to install a huge new pair of solar arrays on the station.

"In the winter of 2000, the first shuttle came up while we were there. They brought large solar panels to give us a lot more electrical power. The shuttle docked for just a week, and they had two astronauts go outside on four space walks to hook up the electrical panels and make sure that all the connections were properly made. These big wings gave us enough electricity for about half a dozen houses."

Shepherd had spotted the shuttle when it was still many miles away from the station, and found it an unreal-looking sight as it drew closer. With no way of sensing its scale, it looked more like a model than a huge spacecraft to him. Finally, he heard and felt a very slight bump as the shuttle docked.

It would take six days and three space walks before until the hatches between the shuttle and the station were opened. While the solar wings were being hooked up outside, Shepherd and his crew were monitoring the station's systems very carefully to ensure all was working smoothly, wiring the system from the inside. Finally, with the pressures equalized, Shepherd could properly welcome his first guests and begin unloading the supplies they had brought with them. In true Navy tradition, he rang the ship's bell to announce their arrival onboard — "that is how you do arrivals on ships, and this is now a tradition in space." He floated into Endeavour to inspect the solar arrays through its windows. He was surprised how frail they looked in contrast to their size. He also noticed how he had become used to the relative spaciousness of the station — the shuttle seemed small and cramped to him. The next day Endeavour undocked, and Shepherd's crew were on their own again, with yet another large consignment of equipment to store.

"The white bags that we use to store equipment come up in various lockers in the shuttle's logistics modules. In the IMAX movie you can see that there are numbers written on the bags in black magic marker pen. I marked all of those bags, because I was looking at the tiny labels on them — you couldn't read the damn things! I was looking at them from six feet away, looking at a list of bags with eight-digit numbers. I had enough of it one day, got my marker pen out and marked all the bags!"

Shepherd used the unique advantages of weightlessness when he could to keep the process moving as fast as possible.

"It's kind of cool — when you want to go somewhere, you just float down there. It's a pretty strange feeling. It's like being in a swimming pool, but you don't get wet, and you can go wherever you want. I could push off the wall with two fingers and fly right across the room. Through the rest of the winter of 2000 we were installing more equipment, fixing the occasional thing that got broken."

At the end of the year came word that the next shuttle launch to the station would be delayed, while potential problems with the shuttle's solid rocket boosters were checked out. Shepherd was happy to extend the mission a little longer — both himself and Gidzenko were used to such delays in the military, and besides, he stated, Krikalev was "the expert on flight delays" following his extended mission on Mir due to the collapse of the Soviet Union. Shepherd planned to use the extra time to prepare for the installation of the large laboratory the shuttle would be bringing. His biggest concern, he joked, is that they were running out of movies to watch — they would soon have to turn the sound down and mouth the words, as they had memorized them all. Despite the delays, Shepherd was enjoying life in space.

"The food was one of the highlights of our day. We tried to gather together and have breakfast, lunch and dinner around a little table. We used that as a way to discuss how the day was going and to plan what we were going to do next. A little box that we had would take moisture out of the air from the air conditioning — we would clean it up and drink it. You can play with your food in space, and it's okay — we'd spin bags of tea around. You can eat upside down — it doesn't matter — your body doesn't really know the difference.

"Sleeping in space is very relaxing, and fun. Most people like to be restrained somehow, and we had little sleeping bags that we would jump into because that was convenient. The only other thing was, the environment was a little bit noisy so we had to wear earplugs. We had a sunrise and sunset every ninety minutes, so we either had something over our eyes or were away from the windows where we'd get bright sunlight and be up all night. Sleeping was easy to do, as we had long days and short nights. We'd jump in our sleeping bags, kill the lights and we'd be out until 6 a.m. the next morning."

At Christmas time, the crew sent holiday greetings to Earth. With echoes of the Christmas message sent from the Apollo 8 mission to the Moon, the crew shared their sense "that the human spirit to do, to explore, has no limit... and the hope that our feelings of good will and purpose onboard 'Alpha' may enrich the holiday spirit for all — on the good planet Earth." Shepherd also hung out some Christmas stockings, a tradition that initially bemused his Russian crewmembers, and exchanged Christmas presents with them.

In the days before the New Year, Gidzenko redocked the Progress M1-4 supply craft, this time with no problems, and the crew discussed how to film more footage for the IMAX movie. Shepherd had found that to film the four scenes possible with one can of film had tied up two crewmembers for five hours during the last shuttle's visit — not including any crewmembers actually in the shot. During the next shuttle's visit it was planned to shoot three cans of film, so the crew needed to make the setup and shooting process a lot faster.

"The IMAX camera was up there for about two years. We trained on the ground with similar training cameras. We would get a couple of magazines, go to mockups and practice shooting all the scenes shot in space, either inside the space station, or the exterior shots that were operated by astronauts. We were a semi-professional film crew, though we did not get paid scale! The IMAX camera is very large — it weighs over 100 pounds. Even in weightlessness, dealing with this film system and coming back with good product is very challenging. It is also important to remember that making a movie in space is like asking a surgical team in the middle of open heart surgery to stop what they are doing and film it. Getting this done was really secondary to our central job of building the space station. Getting good scenes in the can was very arduous; just to shoot a twenty second segment, which was about the average, took about an hour and a half of preparation by the crew. We would set up the lighting, configure the station, load the camera, getting the camera moves down, the actors in place, rehearsing the action, making sure they had the same clothes on as in the scene before, and on and on! It was a real effort. Lighting was a huge issue with this camera because of the large format. You'll see some interesting camera moves. I remember seeing some of the initial shots of this, and people were saying it could not be real — that it had to be done in some backlot up in Hollywood."

On the first day of 2001, Shepherd wrote a poem as the first entry in the ship's log, describing the station sailing on a journey "beyond realm of sea voyage or flight," with electronic pulses instead of a compass, solar panels set as sails, leaving a wispy, invisible wake as they traveled "beyond lines where sky meets the dawn." The entry, full of the spirit of pioneering sea voyages, ended with the line "let the real 'Space Odyssey 2001' proceed."

In the first few days of the year 2001, the crew watched the movie versions of Arthur C. Clarke's "2001" and "2010" novels — the latter describing a joint American-Russian mission . The irony was not lost on Shepherd, who remarked how strange it was to watch a movie about a space expedition when you are on one at that very moment. A couple of days later, Shepherd entered in the ship's log: "Put some more engine on this thing and send up that Mars vector."

There were further parallels to seafaring when the crew made a thermal blanket for the air conditioner's compressor, so that water would not condense on its surface. Using needle and thread, they created a blanket made out of cargo bags, a "seamanship session" that Gidzenko said qualified him for a day job as a sail maker. Later that month, Shepherd struck the ship's bell to commemorate the fifteenth anniversary of the Challenger tragedy.

On February 7th, space shuttle Atlantis was launched, carrying the first science laboratory to Alpha. Remarking on the fact that it would take the shuttle two days to reach the station, Shepherd quoted from American naval hero John Paul Jones, "a stern chase is a long chase." It had also been a long voyage for the Destiny science and technology module, a work area that would finally allow science experiments to begin on the station. For the time being, however, it would be without science racks, their weight requiring that they be launched on a separate, later mission.

"A second shuttle came up in the middle of our mission. They brought a schoolbus-sized module — the laboratory. They used a robot arm to bring it to us and lock it down on the space station. They then had three sets of space walks — astronauts went outside and hooked up the plumbing, the wiring and the computer lines, so we could talk to it. I was inside with a shirt on, looking at Bob Curbeam outside in a space suit. It was minus two hundred degrees outside. That went on for a week, and then finally we could open the hatch between the shuttle and the space station."

With the hatches open, the shuttle crew moved further supplies into the station, while the station crew began to connect the Destiny laboratory's systems to the rest of the station. With the shuttle crew also working on the station's engineering tasks, Shepherd was delighted with the amount of work being done, remarking "all is very much like the SEAL saying — two shooting, two looting, and one taking pictures." Shepherd found the lab spacious, clean and well-lit, though he mused that this could not last very long. In the meantime, the Progress M-14 cargo ship was filled with as much trash as possible, after challenging struggles cutting up large blocks of foam to fit. Shepherd was relieved that, for the first time in months, some station decks were visible and not covered in redundant equipment. On February 8th, the cargo ship was undocked and deorbited over the Pacific Ocean. Shepherd noticed how fast it departed compared to a shuttle, and watched it shrink to a black speck. Although they were on the night side of the Earth, the ground below was covered in snow and cloud, making it possible to watch as the supply ship disappeared into the gloom.

The crew also captured some great IMAX footage during the visit — "Sergei does his usual IMAX magic ... Lab window, EVA crew, sunrise — it doesn't get much better," Shepherd remarked. Atlantis undocked on February 16th, landing in California four days later.

The shuttle visits had given Shepherd his biggest scares of the mission so far, though it was not, as some might have guessed, worries over issues like "space junk" impacting the station.

"We never ran into any space junk per se, though it is out there. There is stuff in low Earth orbit, all the way from paint flakes to large pieces of spacecraft. Fortunately there is not a lot of the big stuff out there. We do extensive analysis on this problem. We can see the big stuff. For the smallest stuff, we have armor plating on the spacecraft to avoid. There is a band of things in the middle that are big enough to hurt us, but small enough that we can't detect them with our search radars to stay away from them. The chances that we would have an impact that would damage the station to the point of risking the crew would be one every five hundred years. The thing I was most scared of in space was being on camera during press conferences, with millions of people watching on Earth! We would do these live broadcasts sending stuff down. I don't know why, but for some reason I would get really wrapped up ensuring that everything was in place — everything was working, we had the right clothes on, I had my script. I was running around like a crazed astronaut inside the module. That was some of the most anxious stuff I did — I can't explain it! Trying to do a live press conference in Russian — you don't know what the questions are, the comm is not very good and even if you really hear it clearly you might not understand what the person is asking. They might be using a vernacular that you don't quite catch. That was stress, right there — all of Europe is watching, don't blow it!"

On February 24th, the crew boarded the Soyuz TM-31 spacecraft and backed it away from the space station. Half an hour later they redocked at a different port, meaning another Progress supply ship would be able to dock. Shepherd had concerns over the failures in consistent communications with mission control at this time, but was very impressed with Gidzenko's flying skills as they quickly moved away from the docking adapter with little rotation, drifted out to thirty meters then flew up the underside of the station. With a mild bump, they docked with the station once again. Four days later, a new Progress supply vehicle docked with the station, bringing more supplies.

On March 8th, space shuttle Discovery was launched, and docked with Alpha one day later. It was bringing up the multi-rack, Italian Leonardo module.

"In March of 2001, the shuttle Discovery came up, to swap out the crews. In addition, we had a big module that we would use to move large things from the space station back to the ground, and from the ground to space. There was a lot of gear in the module that needed moving into the station."

As well as using the module to transfer equipment, Discovery was bringing a robot arm platform — and a new resident crew. After four and a half months in space, this shuttle would be Shepherd's ride home.

Until March 19th, Shepherd worked on making sure all was ready to hand over the station to the next commander, cosmonaut Yuri Usachev. He tried some new lighting techniques to create some more IMAX footage, and eagerly awaited the opportunity to see if they had worked. Even on his last day as commander, he was still discovering solutions to technical problems, though reluctantly had to admit "it is time to leave these details to the next crew."

Sticking with naval lore to the last, he observed the tradition of designating individuals who should be considered "plankowners" of a newly sailed vessel. Shepherd knew that for a continuously operating space station, the process of handing over command to the next crew would be one of the big differences from shuttle operations. In his final entry in the ship's log, he stated:

"Change of command is an ancient naval tradition — the passage of responsibility for mission, welfare of crew, and integrity of vessel from one individual to another. We are on a true space 'ship' now, making her way above any Earthly boundary. We are not the first crew to board Alpha, or the last to depart. But we have made Alpha come alive. We gave her a name, and put substance to the ideas — that our crews can work together as equals, and our countries as partners. We pass to your care Alpha's log, with the hope that many successful entries are recorded here, that explorations carried out onboard are prodigious, and discoveries wondrous. May the good will, spirit, and sense of mission we have enjoyed onboard endure. Sail her well."

With that, the ship's log was formally handed over, command was transferred, and the hatches between the shuttle and station closed.

"We swapped out with the second expedition, got on the shuttle, undocked, and rode around the station — the first time we had seen it from a distance. We landed about a day and half later down in Florida. I would have landed in either the Russian capsule or the shuttle. The shuttle is a lot more convenient because you land right at the space center. With the Russian landing system, you are out in the middle of nowhere. It is a much steeper descent — it is a ballistic capsule with thermal protection, so it does not need to have a more benign angle. The Soyuz landing is done near the launch area in Kazakhstan — it looks like Yuma, Arizona. Flying down to Kazakhstan from Moscow, there is not a tree in sight — it is just flat desert. There aren't too many places I can think of where there are no trees within 600 miles! It is one big landing zone to bring the capsule in.

"The most emotional moment for me was getting back to Florida, getting off the orbiter, having to wait almost two hours to get everything out of the orbiter, getting everybody out of their spacesuits. You are in a large mobile lounge. Then you get to see your wife — and that was the most emotional moment. What was I going to look like to her — I looked kind of scruffy!"

The return from orbit proved a nail-biting end to the whole mission for Beth Shepherd.

"The most anxious moment was when they were supposed to land. They always try to land in Florida, and we did not know until five to ten minutes before landing whether they would, because there was a problem with the winds. Not only did I want to see him, but I was also supposed to be doing the rehabilitation for him. I was trying to figure out that if I drove to Orlando and caught a flight, I could be at Edwards Air Force Base four hours after they had landed. It was a tense moment, waiting until the last minute until we finally realized they would land in Florida."

Before the flight, Bill Shepherd had stated that, this being his fourth mission, he would be looking forward to having a good landing far more than a good launch — to be back safely, with a good mission behind him, having "left a good ship in orbit." He had achieved this goal beyond what many had dared hope for.

"We stayed in Florida for about a day then went back to Houston, and got to meet with friends, family, and a lot of people who helped us on our flight. And that was our flight!"

The political disputes between the partners had not ended with this successful flight, however — with the Mir space station deorbiting just a few days after Shepherd's return, the Russians now planned to send Dennis Tito to the ISS. Shepherd was all for private citizens going into space, as long as they understood the risks. It could also be one way to ensure that the Soyuz spacecraft kept flying to the station.

"The Soyuz has two functions right now. One is that it carries crews to orbit occasionally, and the second is that it is used as a lifeboat. In the second role, we try and have Soyuz attached to the space station to the end of their service lives. They have propellants in them — basically hydrogen peroxide — that we have to keep under a certain pressure and let a little bit escape. They boil off slowly and over a period of time you lose them. After about six months, we get to the redline of how much re-entry propellant we need to get back. It may not be exactly the time we want to trade the crews out, because right now the crews are running in increments of four to five months. So we generally change crews on the shuttle. We change the Soyuz with special crews just to fly it up, get in the old Soyuz and bring it down — they are called taxi crews. Mark Shuttleworth was on a taxi flight.

"Beth and I were in Russia with Dennis Tito — he did not fly when we were in space, he flew shortly thereafter. I thought he was an okay guy, and particularly so because he had been a former NASA employee — he was clearly a big space nut. I am not really against having people fly in space because they can afford to do it. It is part of having commerce and business in space, which in one sense is good. I do think that we have to have these people fully aware that this is a risky thing. It is not for everybody, and there is no guarantee that you are going to come up and back in one piece. They have to understand that. Additionally, we are in the middle of finishing the construction — it is not done yet. These folks who show up for the 'tour,' if you will, need to be able to mesh with the environment up there, not get in the way, and really be part of the team. As long as they do that, I think that it is acceptable. It is a step, a bit like the way the West was opened up, and railroads were laid down. The government played a large role in enabling that infrastructure — such as land grants and protecting the railroads. Then the government got out of the way, and business proceeded. I think that we will see the same thing in space. Unfortunately, it is not going quite as fast as we would like — but we will have that evolution. Having space tourism is a part of that."

Shepherd has no plans to return, however — he's happy to be out of the politics of the project for good. Not long after his flight, he left both NASA and the Navy, though he is still working with the latter.

"I came back to San Diego after my flight to finish my Navy career with the SEALs. I retired in December after a thirty-year career. I am still working with the SEALs, doing a job I came for in the summer, although I am a contractor, and I will continue to do that for a while. One of the problems I think we have right now is that NASA, along with the other space agencies who are involved in this, are stuck in a Byzantine, eighteenth century squabble about who owns what. It is very counterproductive, and all wrapped around the national politics of each country. What we are trying to do in space is bigger than that. Unfortunately, we don't have a whole lot of people in Washington who understand that. That is why I am Bill Shepherd, civilian, and happy to be!"

Despite all the political, technical and budgetary setbacks over the years, he is extremely proud of what he and his crew achieved in their pioneering first voyage.

"The space station is still very much in the news, and we are still having big budget problems. It is not perfect, but it is up there, it is working, and I would bet that it is certainly adequate. It is starting to do some really good science. But the most important thing is that, tonight, we have three people up there — Americans and Russians — working together in an unprecedented international cooperative effort. There are sixteen countries involved — the largest project ever done of this magnitude outside of wartime. Some are our former cold war enemies. I flew with Russian fighter pilot Yuri Gidzenko; he and I would look out of the window in the afternoon, going over places in Asia where he stood on alert in the cockpit of his MIG-21. Next revolution around the Earth, I would show him places in the Far East where I worked and trained as a Navy SEAL. This is really monumental stuff. We are building a culture in space that is absorbing the better parts of things the United States and the Russians have learned. It is kind of hard for some of the old guard in both countries to accept and understand this, but I really think that this is one of the huge strengths of what we are doing. The point is that this can be done, we have proved we can make it work. The door is open to doing bigger things — let's get on with it!"